Introduction and Overview

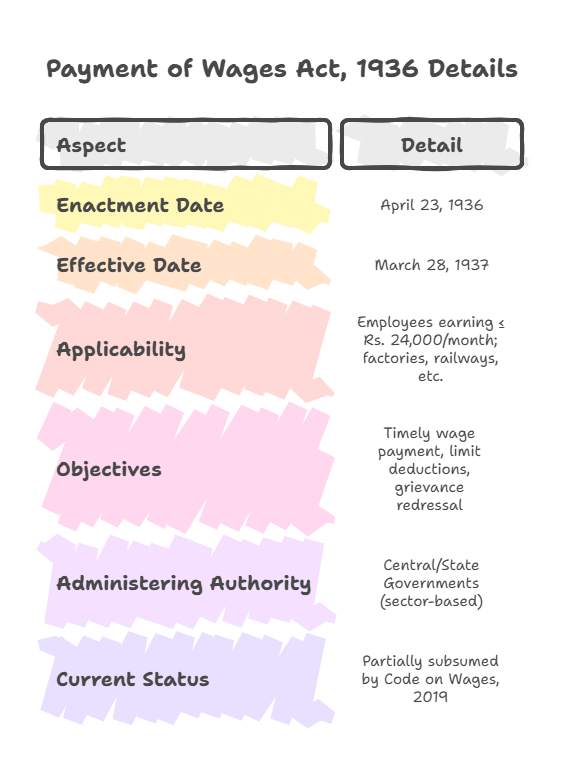

The Payment of Wages Act, 1936, is a pivotal labor legislation in India, designed to ensure timely and full payment of wages to workers while preventing unauthorized deductions, thereby safeguarding their financial security. Enacted on April 23, 1936, and effective from March 28, 1937, it primarily targets low-wage workers in industrial and other specified establishments, such as factories, railways, mines, and plantations. The Act applies to employees earning up to Rs. 24,000 per month (as amended in 2017), covering both permanent and contract labor. Administered by state and central governments (based on the sector), it mandates payments in legal tender (coin, currency, cheque, or bank transfer) within stipulated timelines, regulates permissible deductions, and provides mechanisms for grievance redressal. Its objectives include promoting industrial harmony, preventing exploitation, and ensuring workers receive their rightful earnings without delays or arbitrary cuts. For UPSC EPFO and ALC exams, the Act is a core component under “Industrial Relations & Labour Laws,” with significant weightage due to its focus on wage protection and integration into the Code on Wages, 2019 (effective in phases from 2025). The Act remains relevant for addressing issues in organized and unorganized sectors, especially with recent digital payment reforms.

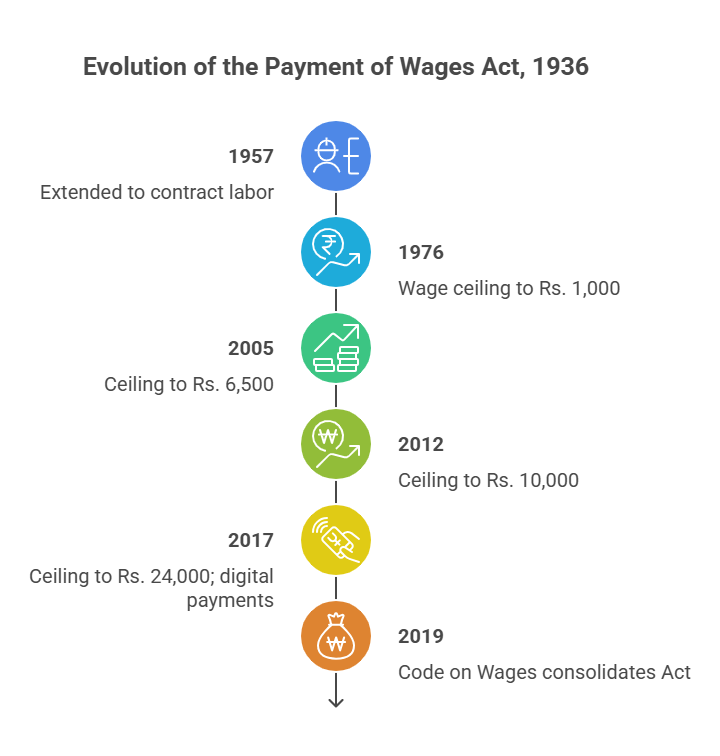

Historical Background and Evolution

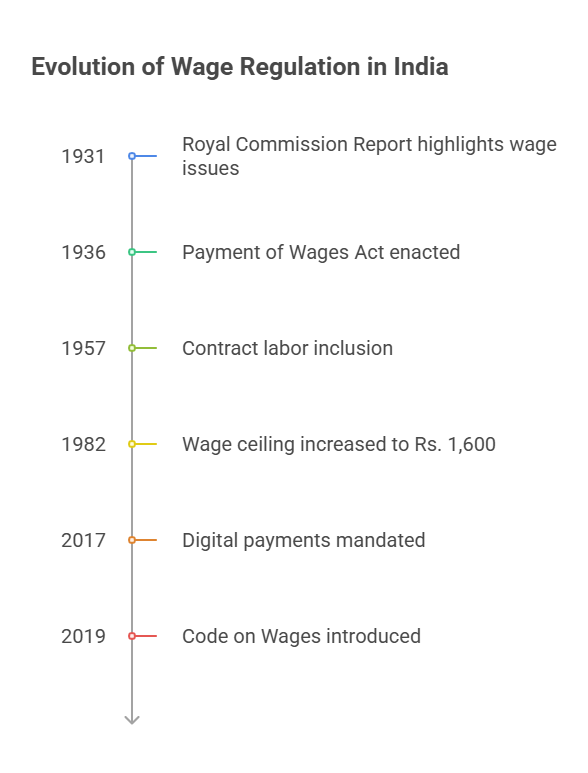

The Payment of Wages Act emerged during British colonial rule to address widespread labor exploitation, particularly in factories and railways, where irregular payments and arbitrary deductions were rampant. Influenced by the Royal Commission on Labour (1929-1931) and ILO conventions, the Act was introduced as a Bill in 1933 to standardize wage practices amid growing trade union movements (e.g., Bombay Textile Strike, 1928). Post-independence, it aligned with India’s socialist policies under the Directive Principles (Articles 39, 43), ensuring worker welfare during rapid industrialization in the 1950s. Key amendments include 1957 (contract labor inclusion), 1964 (wage ceiling to Rs. 400), 1976 (to Rs. 1,000), 1982 (to Rs. 1,600), 2005 (to Rs. 6,500), 2012 (to Rs. 10,000), 2015 (to Rs. 18,000), and 2017 (to Rs. 24,000, digital payments mandated). The 2017 amendment allowed cheque or bank payments for specified establishments, aligning with India’s digital economy push post-demonetization (2016). The Act’s enforcement resolves over 1 lakh claims annually, with the Code on Wages, 2019, introducing a national floor wage and further streamlining provisions for broader coverage, including gig workers, by 2025.

Evolution Phases

- Pre-1936: Ad hoc wage practices; colonial exploitation.

- 1936-1947: Initial focus on factories, railways.

- Post-Independence (1947-1990): Expanded scope, wage ceiling increases.

- Post-Liberalization (1991-2019): Digital reforms, broader applicability.

- Code on Wages Era (2020-2025): Consolidation, floor wage, gig worker inclusion.

Definitions and Scope

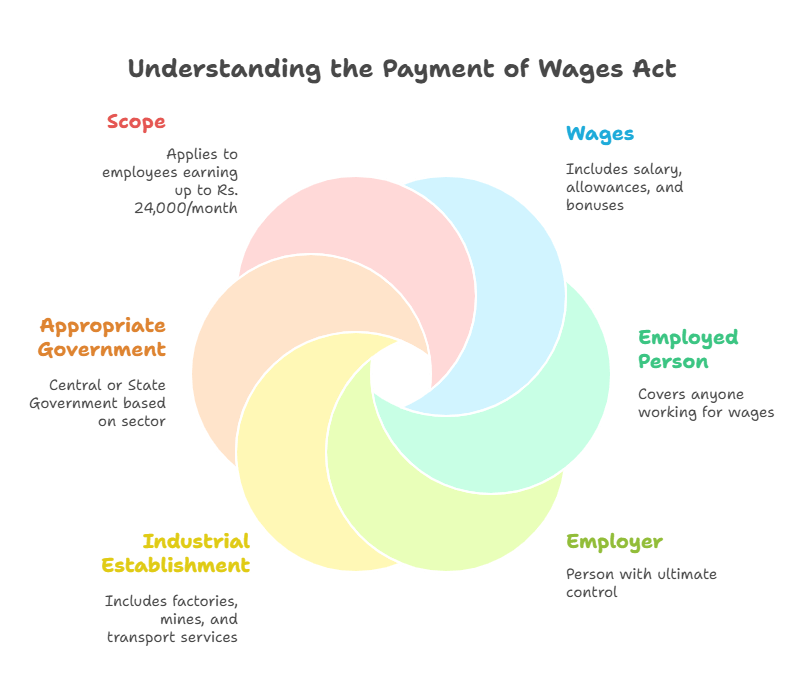

Section 2 of the Act defines key terms to ensure clarity and enforcement. “Wages” (Section 2(vi)) include all remuneration (salary, allowances, overtime, contractual bonuses) but exclude gratuity, travel allowances, pension contributions, and house rent allowance (unless part of contract). An “employed person” (Section 2(i)) covers anyone working for wages, including legal heirs for claiming unpaid wages, and extends to contract labor. “Employer” (Section 2(ia)) is the person with ultimate control, such as owners or managers, including heirs. “Industrial or other establishment” (Section 2(ii)) includes factories, railways, mines, plantations, docks, transport services, and notified entities like shops or hotels. The “appropriate government” (Section 2(iii)) is the Central Government for railways and mines, and State Governments for others. The Act applies to the whole of India, targeting employees with wages up to Rs. 24,000/month, with no minimum employee threshold (unlike EPF Act’s 20). Exclusions include supervisory roles above the ceiling and certain public servants. The scope covers both organized and notified unorganized sectors, with state governments empowered to extend applicability via notifications.

Scope Details

- Applicability: Employees ≤ Rs. 24,000/month; no employee count limit.

- Coverage: Factories, railways, mines, plantations; extendable to shops, hotels.

- Exclusions: High-wage supervisors, defense forces, certain government entities.

Responsibility for Payment of Wages

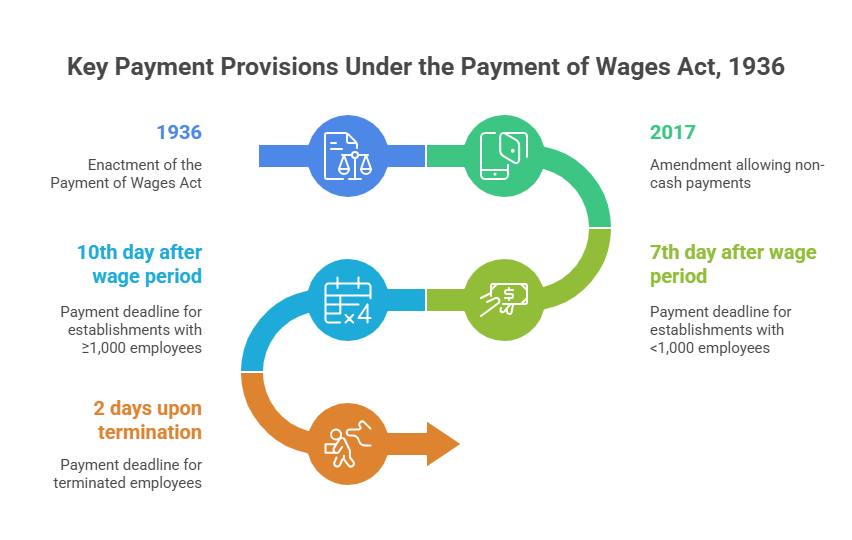

Section 3 mandates that employers are responsible for paying wages to all employed persons, ensuring full and timely disbursal. In large establishments, a nominated person (e.g., manager) may handle payments, but ultimate liability remains with the employer. For contract labor, the principal employer is liable if the contractor fails, preventing evasion in subcontracted setups like construction or manufacturing. Section 4 requires wage periods not to exceed one month, ensuring regular payments (e.g., monthly or fortnightly cycles). Section 5 sets strict timelines: wages must be paid by the 7th day after the wage period for establishments with fewer than 1,000 employees, and by the 10th day for larger ones; upon termination, payment is due within 2 days. Payments must be made on working days, in legal tender (coin, currency, cheque, or bank transfer), with the 2017 amendment allowing governments to mandate non-cash modes for specified sectors to enhance transparency. These provisions reduce financial hardship and ensure accountability, with courts emphasizing strict compliance.

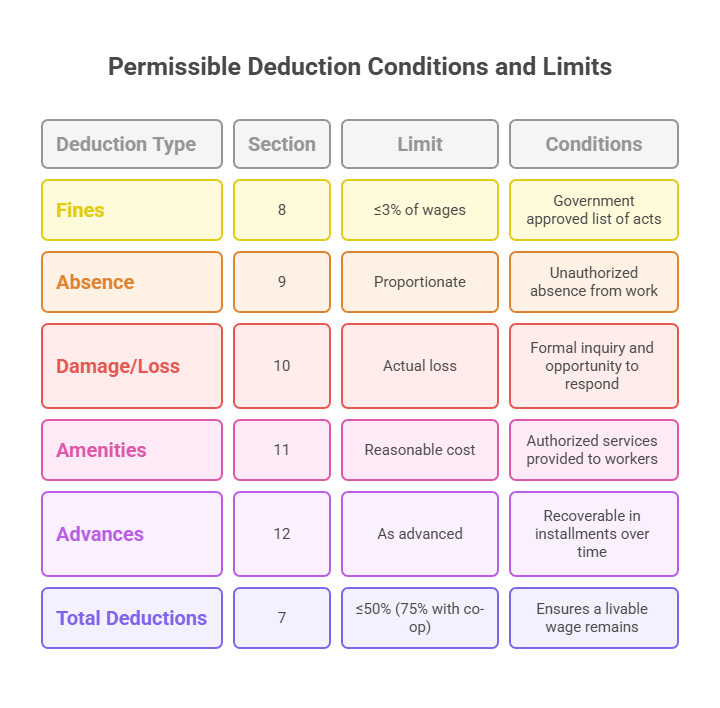

Deductions from Wages

Section 7 restricts deductions to specified categories to protect workers’ earnings. Permissible deductions include fines, absence, damage/loss, amenities, advances, taxes, provident fund contributions, co-operative dues, and court-ordered payments. Total deductions cannot exceed 50% of wages (75% if co-operative dues are included), ensuring workers retain a livable income. Section 8 governs fines, limited to 3% of wages, requiring a government-approved list of acts/omissions, a show-cause notice, and imposition within 1 year of the offense. Fines must fund worker welfare (e.g., canteen facilities). Section 9 allows proportionate deductions for unauthorized absence. Section 10 permits deductions for damage/loss due to negligence, after inquiry and opportunity to respond. Sections 11-13 cover amenities (e.g., housing), advances (recoverable in installments), and overpayment recovery (limited to 3 months prior). These rules balance discipline with fairness, preventing exploitative cuts.

Deduction Limits

- Fines: ≤3% wages; approved list, welfare use.

- Absence: Proportionate to time absent.

- Damage: Actual loss after inquiry.

- Total: ≤50% (75% with co-op).

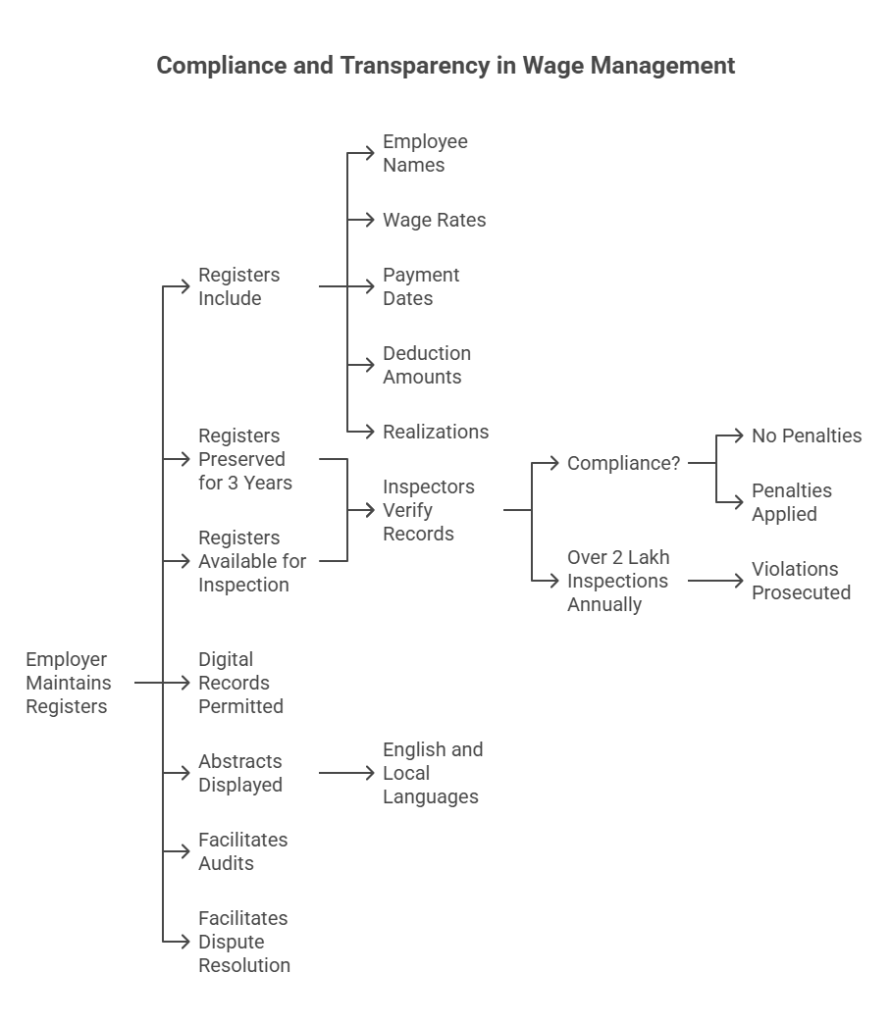

Maintenance of Records and Registers

Section 13A mandates employers to maintain detailed registers for wages, fines, deductions, and advances, preserved for 3 years and available for inspection.

These include employee names, wage rates, payment dates, deduction amounts, and realizations, ensuring transparency. Rules under Section 26 prescribe forms (e.g., wage register with signatures/thumb impressions).

Section 25 requires displaying abstracts of the Act and rules in English and local languages at workplace entrances to inform workers.

Inspectors (Section 14) verify records, with non-compliance attracting penalties.

Digital records are permitted post-2017, aligning with e-governance initiatives.

Over 2 lakh inspections annually ensure adherence, with violations prosecuted under Section 20.

These records facilitate audits and dispute resolution, reducing wage-related conflicts.

Required Registers

Advance Register: Loan amounts, recoveries.

Wage Register: Payment details, signatures.

Fines Register: Acts, amounts, welfare use.

Deduction Register: Absence, damage details.

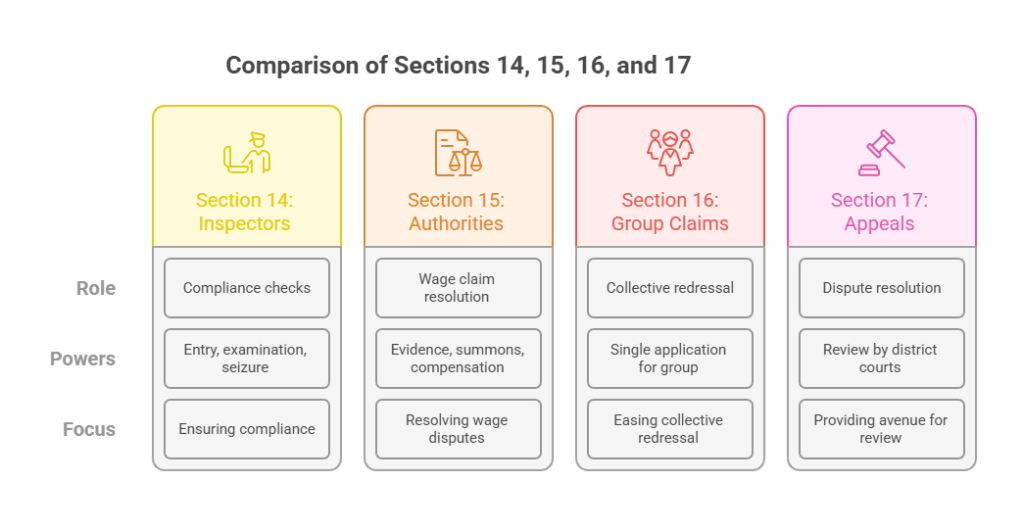

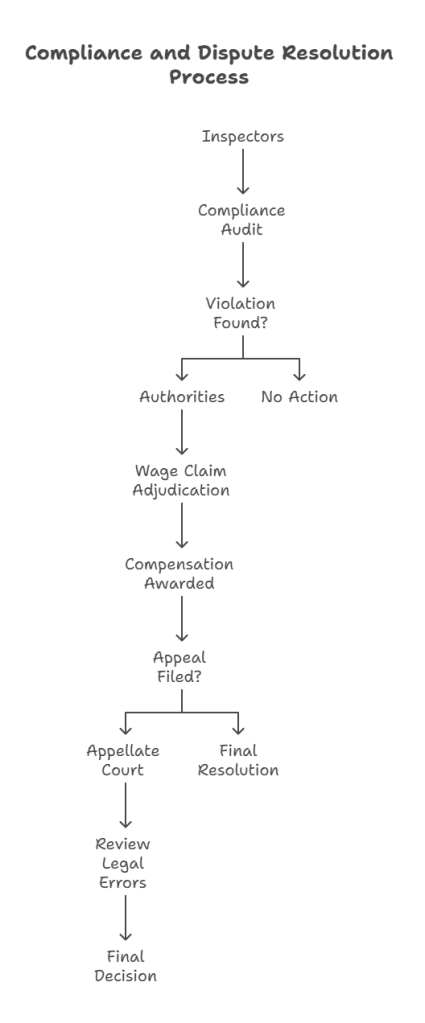

Authorities and Enforcement

Section 14 appoints inspectors as public servants with powers to enter premises, examine records, question employees, and seize documents to ensure compliance. They conduct over 50,000 inspections yearly, resolving thousands of violations. Section 15 establishes authorities (e.g., labor commissioners, magistrates) to hear claims for delayed or deducted wages, with powers akin to civil courts for evidence and summons. Authorities can award compensation up to 10 times the deducted amount, ensuring deterrence. Section 16 allows single applications for group claims, easing collective redressal. Appeals (Section 17) lie to district courts within 30 days, with employer appeals requiring deposit of awarded amounts. The system emphasizes quick justice, with digital filings introduced post-2020 for efficiency.

Authority Roles

- Inspectors: Compliance audits, investigations.

- Authorities: Adjudicate wage claims, award compensation.

- Courts: Appellate jurisdiction for disputes.

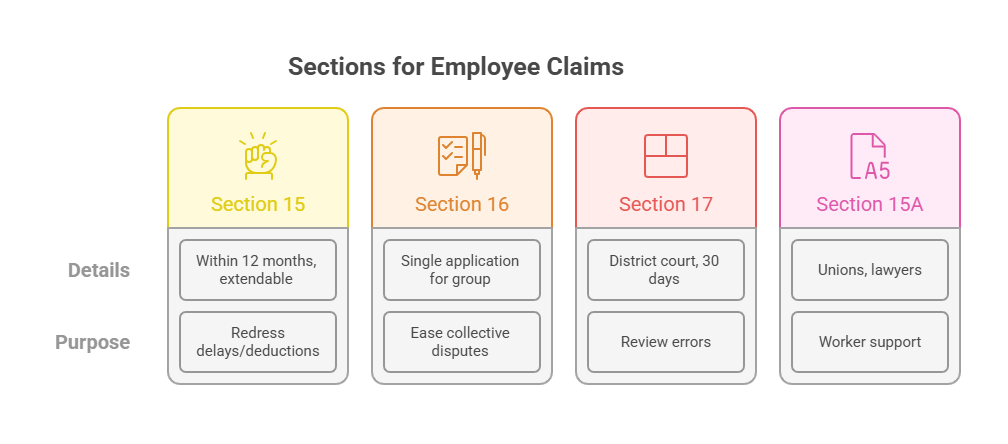

Claims and Appeals

Section 15 enables employees or their representatives (unions, inspectors) to file claims for wrongful deductions or delayed wages within 12 months, extendable for sufficient cause. Authorities can order payment of dues plus compensation (up to 10 times deductions), ensuring punitive measures for violations. Section 16 facilitates group claims, reducing individual burden in factories or mines. Appeals under Section 17 go to district courts, requiring employers to deposit awarded amounts unless waived. Section 15A allows unions or legal practitioners to represent workers, enhancing access to justice. Claims processed digitally via labor portals since 2020 resolve 70% cases within 6 months. The system protects vulnerable workers, with courts interpreting “wages” broadly to include contractual bonuses.

Claims Process

- File claim within 12 months.

- Authority hearing with evidence.

- Order for dues/compensation.

- Appeal to district court (30 days).

- Enforcement as fine/arrears.

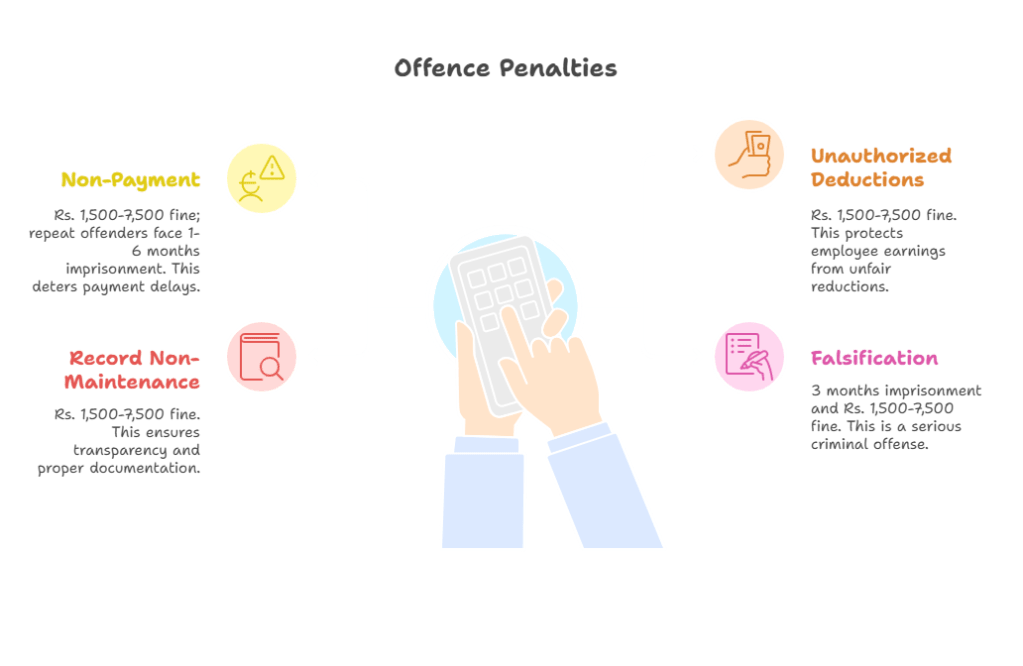

Penalties and Offences

Section 20 outlines penalties to deter violations. Non-payment or delayed payment attracts fines of Rs. 1,500-7,500 for first offenses, with repeat offenses leading to 1-6 months imprisonment and fines of Rs. 3,750-22,500.

Unauthorized deductions incur Rs. 1,500-7,500 fines. Failure to maintain registers or falsification leads to Rs. 1,500-7,500 fines or 3 months imprisonment.

Companies face director liability if involved (Section 20). Cognizance requires complaints from inspectors or sanctioned persons (Section 21).

Section 22 bars civil court suits, directing claims to authorities. Section 23 prohibits contracting out of rights. Over 10,000 prosecutions annually recover dues, with enhanced penalties under the Code on Wages, 2019 (up to Rs. 50,000).

Offence Categories

- Non-Payment/Delay: Fines, imprisonment for repeats.

- Unauthorized Deductions: Fines for unfair cuts.

- Record Violations: Fines, imprisonment for falsification.

Case Laws, Amendments, Conclusion, and Importance

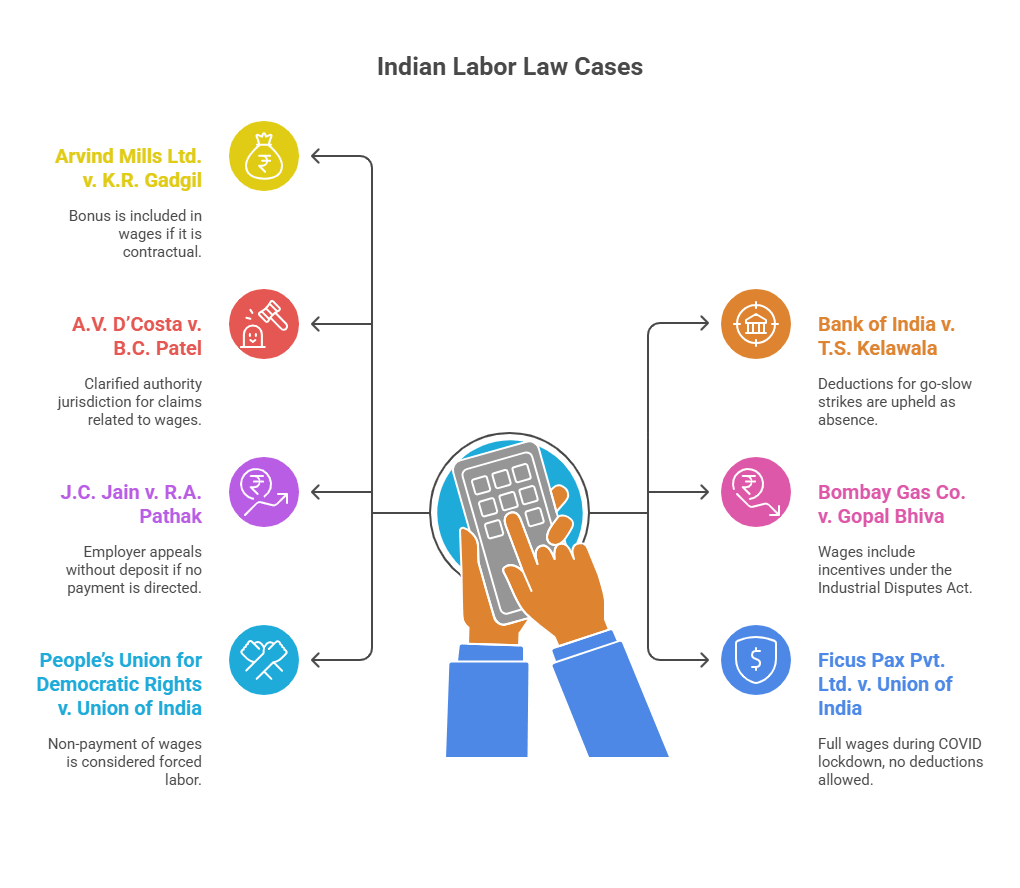

Key Case Laws

- Arvind Mills Ltd. v. K.R. Gadgil (1941): Bonus included in wages if contractual.

- Bank of India v. T.S. Kelawala (1990): Deductions for go-slow strikes upheld as absence.

- A.V. D’Costa v. B.C. Patel (1955): Clarified authority jurisdiction for claims.

- Bombay Gas Co. v. Gopal Bhiva (1964): Wages include incentives under Industrial Disputes Act, linked to Payment of Wages.

- J.C. Jain v. R.A. Pathak (1989): Employer appeals without deposit if no payment directed.

- Ficus Pax Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India (2020): Full wages during COVID lockdown, no deductions.

- People’s Union for Democratic Rights v. Union of India (1982): Non-payment as forced labor.

Amendments

- 1957: Extended to contract labor.

- 1976: Wage ceiling to Rs. 1,000.

- 2005: Ceiling to Rs. 6,500.

- 2012: Ceiling to Rs. 10,000.

- 2017: Ceiling to Rs. 24,000; digital payments.

- Code on Wages, 2019: Consolidates Act, introduces floor wage, gig worker coverage.

Leave a comment