The Nanda Dynasty was a pivotal ruling house of the Magadha kingdom in ancient India, succeeding the Haryanka and Shishunaga dynasties. Known for its immense wealth, vast military might, and centralized administration, the Nanda Dynasty transformed Magadha into a dominant power, laying the foundation for the subsequent Mauryan Empire. Based in Pataliputra (modern Patna, Bihar), the Nandas unified much of northern India but were overthrown by Chandragupta Maurya with the guidance of Chanakya. This study material provides a detailed examination of the Nanda Dynasty’s historical context, rulers, social and economic structure, achievements, cultural contributions, and legacy, with original phrasing to ensure clarity and depth.

1. Historical and Geographical Context

The Nanda Dynasty emerged during the late Mahajanapada period (c. 600–321 BCE), a time of political consolidation, urbanization, and economic growth in northern India. Magadha, already a leading Mahajanapada under the Haryankas and Shishunagas, became a proto-imperial power under the Nandas due to its fertile lands, strategic location, and control over key trade routes.

Key Features:

- Geography: Magadha encompassed modern-day Bihar, parts of eastern Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Bengal, with influence extending to central and eastern India, including regions like Kalinga and Avanti.

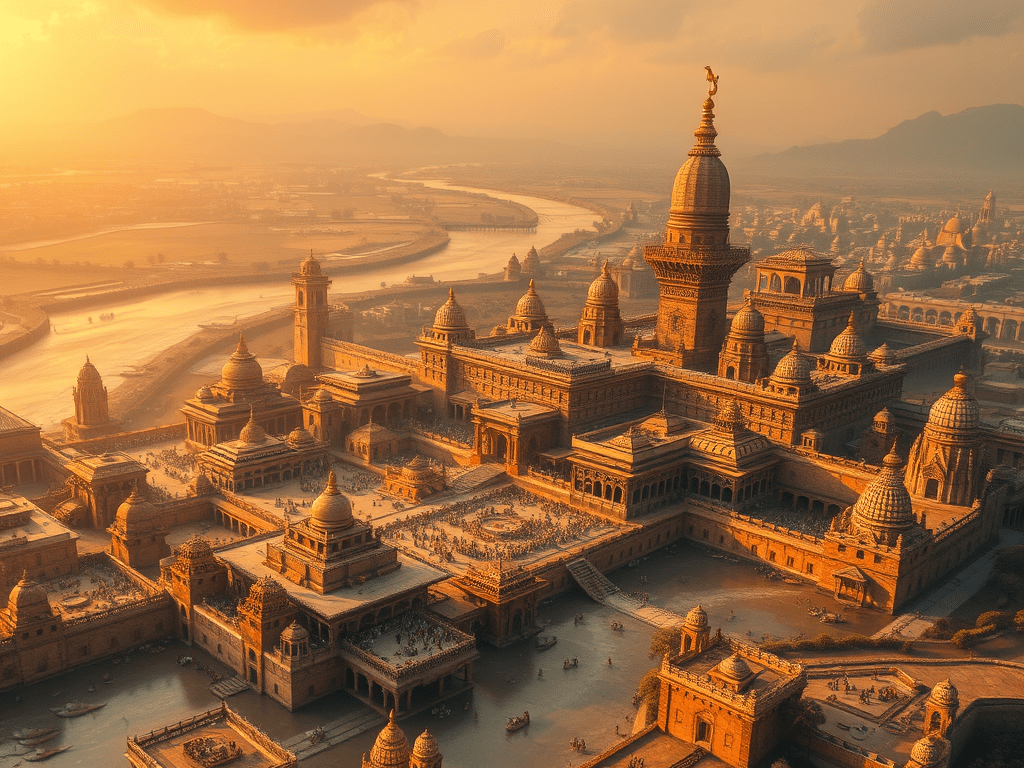

- Capital: Pataliputra, a fortified city at the confluence of the Ganges and Son rivers, was a political, economic, and cultural hub.

- Timeline: c. 345–321 BCE, with slight variations in dates across Buddhist, Jain, and Puranic sources.

- Significance: The Nandas were the first non-Kshatriya dynasty to rule Magadha, achieving unprecedented territorial and economic dominance but facing resistance due to their low-born origins and heavy taxation.

2. Origins and Sources

The Nanda Dynasty’s origins are shrouded in controversy, reflecting the biases of ancient sources:

- Buddhist Texts (Mahavamsa, Digha Nikaya): Describe the Nandas as wealthy but of low birth, possibly Shudra** or Vaishya origin, emphasizing their power and unpopularity.

- Jain Texts (Parishishtaparvan): Portray **Mahapadma Nanda as the son of a barber or a low-caste woman, rising through ambition and conquest.

- Puranas (Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana): List the Nandas as successors to the Shishunagas, noting their non-royal lineage and immense resources. They claim Mahapadma was born to a Shishunaga king and a Shudra woman.

- Greek Accounts: Historians like Curtius Rufus and Diodorus, drawing on Alexander’s campaigns (c. 326 BCE), highlight Magadha’s vast army under the Nandas, referring to their king as Agrammes (likely Dhana Nanda).

- Archaeological Evidence: Excavations at Pataliputra reveal fortifications, urban planning, and Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW), indicating prosperity during the Nanda period.

The Nandas’ non-elite origins challenged traditional Kshatriya norms, contributing to their negative portrayal in Brahmanical sources.

3. Rulers of the Nanda Dynasty

The Nanda Dynasty is primarily associated with Mahapadma Nanda and Dhana Nanda, with the Puranas listing nine rulers, though historical records focus on these two key figures.

a) Mahapadma Nanda (c. 345–329 BCE)

- Background: Regarded as the founder, Mahapadma Nanda (also Ugrasena in Jain texts) was a formidable ruler whose origins are debated. Sources describe him as the son of a barber, a Shudra, or an illegitimate heir of the Shishunaga dynasty, rising through military and political maneuvering.

- Achievements:

- Territorial Expansion: Unified much of northern and central India, annexing Mahajanapadas like Kuru, Panchala, Kashi, Kosala, Vatsa, and parts of Avanti. Extended influence to Kalinga (Odisha) and the Deccan, creating a proto-empire.

- Military Power: Built a massive army, reportedly comprising 200,000 infantry, 20,000 cavalry, 2,000 chariots, and 3,000–6,000 elephants (per Greek accounts). This military strength deterred invasions, including by Alexander the Great.

- Administration: Centralized governance with a bureaucracy managing taxation, trade, and infrastructure. Invested in irrigation projects to enhance agriculture.

- Wealth: Amassed vast riches through land revenue, trade monopolies, and conquests, earning the title Ekarat (sole sovereign) in Puranic texts.

- Legacy: Mahapadma’s conquests and administrative reforms established Magadha as India’s preeminent power, though his low-born status and heavy taxation sparked resentment among elites and subjects.

b) Successors and Dhana Nanda (c. 329–321 BCE)

- Background: The Puranas list eight successors, possibly Mahapadma’s sons, including Pandhuka, Panghupati, Bhutapala, Rashtrapala, Govishanaka, Dashasiddhaka, Kaivarta, and Dhana Nanda. Dhana Nanda, the last ruler, is the most documented, known as Agrammes or Xandrames in Greek sources.

- Achievements:

- Wealth Accumulation: Expanded the dynasty’s treasury, reportedly hoarding vast amounts of gold and silver in Pataliputra.

- Military Maintenance: Sustained the large army, which remained a deterrent against foreign invasions, notably discouraging Alexander’s advance into the Gangetic plains.

- Administration: Continued centralized governance, though inefficiencies and corruption grew under his rule.

- Downfall:

- Dhana Nanda’s oppressive taxation, autocratic governance, and greed alienated subjects, Brahmins, and Kshatriyas.

- Chandragupta Maurya, mentored by Chanakya (Kautilya), capitalized on this discontent, rallying support to overthrow Dhana Nanda c. 321 BCE.

- The Nandas’ resources and infrastructure were absorbed by the Mauryan Empire, facilitating its rapid expansion.

- Fate: Dhana Nanda was likely killed or exiled, marking the end of the dynasty.

4. Social Structure

The Nanda Dynasty operated within the social framework of the Mahajanapada period, blending Vedic traditions with emerging urban and imperial dynamics.

a) Varna and Jati

- Varna System: The fourfold hierarchy (Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, Shudras) persisted, but the Nandas’ non-Kshatriya origins disrupted traditional norms.

- Brahmins: Served as priests, scholars, and advisors, though some opposed the Nandas due to their low birth, as reflected in Chanakya’s rebellion.

- Kshatriyas: Included defeated Mahajanapada rulers, subordinated to Nanda authority, creating tensions.

- Vaishyas: Prospered as merchants, traders, and landowners, benefiting from Magadha’s economic growth.

- Shudras: Performed agricultural and manual labor, with some upward mobility in urban centers.

- Jati (Caste): Occupational groups solidified into hereditary jatis, with shrenis (guilds) organizing artisans, traders, and craftsmen.

b) Family and Gender

- Patriarchal Families: Led by the grihapati (householder), who managed estates, trade, and households.

- Gotra Rules: Governed marriage alliances, strengthening elite networks across regions.

- Women’s Status: Largely confined to domestic roles, though elite women influenced politics indirectly (e.g., through royal marriages). Buddhist and Jain texts mention women ascetics, suggesting limited religious participation.

c) Urban Society

- Pataliputra’s growth fostered a cosmopolitan elite, including shreshthins (wealthy merchants), bureaucrats, and military officers.

- The Nandas’ diverse origins may have promoted inclusivity, but elite resentment persisted, fueling opposition.

5. Economic Life

The Nandas’ wealth was legendary, with their treasury described as one of the largest in ancient India.

a) Agriculture

- Magadha’s fertile Gangetic plains produced surplus crops like rice, wheat, and barley, supported by iron tools and irrigation canals.

- State-sponsored water management projects enhanced productivity, increasing revenue.

- Land taxes (bhaga, typically one-sixth of produce) and other levies were a primary income source, often seen as burdensome.

b) Trade

- Magadha controlled key trade routes along the Ganges, connecting ports like Tamralipti (modern Tamluk, West Bengal) to inland markets.

- Exports included textiles, spices, metals, and gems, traded with Persia, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia.

- Punch-marked coins (silver and copper) standardized commerce, reflecting economic sophistication.

c) Urbanization

- Pataliputra was a sprawling metropolis with wooden fortifications, palaces, and markets, as later described in the Arthashastra and Greek accounts (e.g., Megasthenes).

- Archaeological finds, such as Northern Black Polished Ware and terracotta figurines, indicate advanced craftsmanship and urban planning.

- Other cities, like Rajagriha, remained important administrative and religious centers.

6. Political and Military Achievements

a) Administration

- The Nandas centralized power, establishing a bureaucracy with officials managing taxation, trade, justice, and public works.

- Provincial governors oversaw conquered territories, supported by a network of spies to ensure loyalty.

- The state maintained a standing army and invested in infrastructure like roads and canals, as reflected in later Mauryan practices.

b) Military Power

- The Nandas’ army was one of the largest in the ancient world, with elephants as a key asset, intimidating rivals and deterring invasions.

- Fortifications at Pataliputra and other cities protected the empire’s core.

- Their military strength was a major reason Alexander’s army refused to advance beyond the Beas River (c. 326 BCE).

c) Territorial Expansion

- Mahapadma’s conquests created a proto-empire, unifying diverse Mahajanapadas under a single authority.

- Control over trade routes and resources gave the Nandas economic dominance, setting a precedent for Mauryan imperialism.

7. Cultural and Religious Significance

a) Religious Patronage

- Buddhism and Jainism: The Nandas likely continued Haryanka and Shishunaga patronage, with Jain texts praising Mahapadma’s support for Mahavira’s followers. Buddhist sources are less favorable, possibly due to Mauryan bias.

- Vedic Religion: Brahmins conducted rituals, but the Nandas’ non-Kshatriya status strained relations with orthodox elites, contributing to their unpopularity.

- Syncretism: Magadha’s diverse population fostered coexistence of Vedic, Buddhist, and Jain traditions, with Pataliputra as a religious melting pot.

b) Intellectual Developments

- Pataliputra attracted scholars, fostering debates on philosophy, governance, and economics.

- The period laid the groundwork for Chanakya’s Arthashastra, which reflects Nanda-era statecraft, including taxation and espionage.

- Early Buddhist and Jain scriptures were compiled, contributing to India’s intellectual heritage.

c) Urban Culture

- Pataliputra’s cosmopolitanism supported art, architecture, and literature, with early stupas and monasteries emerging.

- The city’s wealth and diversity attracted artisans, traders, and scholars, creating a vibrant cultural hub.

8. Decline and Legacy

a) Decline

- The Nanda Dynasty fell due to:

- Unpopularity: Heavy taxation, autocratic rule, and Dhana Nanda’s greed alienated subjects, Brahmins, and Kshatriyas.

- Rebellion: Chandragupta Maurya, mentored by Chanakya, exploited this discontent, mobilizing a coalition of disaffected groups to overthrow the Nandas c. 321 BCE.

- Military Overreach: The vast army was costly to maintain, and regional revolts weakened central control.

- Dhana Nanda’s defeat marked the end of the dynasty, with Pataliputra becoming the Mauryan capital.

b) Legacy

- Political Foundation: The Nandas’ centralized administration and territorial unification provided a blueprint for the Mauryan Empire.

- Economic Prosperity: Their wealth and trade networks enriched Magadha, benefiting successors.

- Urban Legacy: Pataliputra remained India’s political and cultural capital for centuries, flourishing under the Mauryas and Guptas.

- Social Mobility: The Nandas’ non-elite origins highlight the potential for social upheaval in ancient India, challenging Kshatriya dominance.

- Historical Debate: Their portrayal as low-born tyrants reflects Brahmanical bias, but their achievements underscore their significance in Indian history.

9. Challenges in Studying the Nanda Dynasty

- Textual Bias: Buddhist, Jain, and Puranic sources reflect religious or political agendas, often vilifying the Nandas to legitimize Mauryan rule.

- Lack of Contemporary Records: Most accounts were written centuries later, blending myth and history.

- Archaeological Gaps: Pataliputra’s early Nanda-era remains are obscured by Mauryan and later structures, limiting direct evidence.

10. Suggested Further Reading

- Primary Sources:

- Mahavamsa, Digha Nikaya (Buddhist texts).

- Parishishtaparvan (Jain text).

- Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana.

- Secondary Sources:

- A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India by Upinder Singh.

- The Age of the Nandas and Mauryas by K.A. Nilakanta Sastri.

- Ancient India by R.C. Majumdar.

- Online Resources:

- JSTOR for ancient Indian history articles.

- Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) reports on Pataliputra.

11. Conclusion

The Nanda Dynasty was a transformative force in ancient India, elevating Magadha to unparalleled power through conquest, wealth, and centralized governance. Mahapadma Nanda’s empire-building and Dhana Nanda’s vast resources showcased Magadha’s potential, but their unpopularity and non-elite origins led to their overthrow by Chandragupta Maurya in c. 321 BCE. By unifying northern India and fostering economic prosperity, the Nandas set the stage for the Mauryan Empire, leaving a lasting legacy in India’s political, economic, and urban history. Their brief but impactful rule highlights the dynamic interplay of power, wealth, and social change in ancient India.

Leave a comment