The constitutional developments in British India during the early 20th century represented incremental reforms aimed at addressing Indian demands for greater representation while maintaining British control. Key legislations included the Indian Councils Act of 1909 (Morley-Minto Reforms), the Government of India Act of 1919 (Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms), and the Government of India Act of 1935. These acts evolved from moderate petitions by the Indian National Congress to more substantive changes influenced by wartime contributions and nationalist pressures. They introduced elements of self-governance, such as expanded legislatures and provincial autonomy, but were often critiqued for their limitations, including communal electorates and reserved powers. Collectively, these reforms shaped the trajectory toward independence, fostering political awareness and institutional frameworks that influenced post-1947 governance.

Indian Councils Act, 1909 (Morley-Minto Reforms)

Enacted on May 25, 1909, this act, named after Secretary of State John Morley and Viceroy Lord Minto, sought to placate moderate nationalists by expanding legislative councils and introducing limited Indian participation. It responded to the Swadeshi Movement and the 1907 Surat Split in the Indian National Congress, aiming to associate Indians more closely with administration without conceding real power.

Key provisions:

- Expansion of Councils: The Imperial Legislative Council increased from 16 to 60 members, with provincial councils enlarged (e.g., Bombay and Madras to 50 members). Non-official majorities were introduced in provincial councils.

- Elective Principle: Indirect elections were formalized, allowing Indians to elect members through local bodies, universities, and chambers of commerce. However, the franchise remained restricted to propertied classes.

- Separate Electorates: Muslims received reserved seats and separate electorates, where only Muslims could vote for Muslim candidates, marking the introduction of communal representation.

- Powers of Councils: Members could discuss budgets, ask questions, and move resolutions, but lacked veto power over legislation. The executive retained overriding authority.

- Indian Representation in Executive: One Indian member was appointed to the Viceroy’s Executive Council (Satyendra Prasanna Sinha as Law Member) and to provincial executive councils.

These reforms aimed at “rallying the moderates” but were criticized for dividing communities and perpetuating British dominance.

Government of India Act, 1919 (Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms)

Passed on December 23, 1919, this act implemented recommendations from the 1918 Montagu-Chelmsford Report, influenced by India’s World War I contributions and the Home Rule Movement. Secretary of State Edwin Montagu and Viceroy Lord Chelmsford envisioned “responsible government” through gradual devolution, establishing dyarchy in provinces.

Key provisions:

- Dyarchy in Provinces: Subjects were divided into “transferred” (e.g., education, agriculture, health) managed by Indian ministers accountable to legislatures, and “reserved” (e.g., finance, police, justice) controlled by the governor and executive council.

- Bicameral Central Legislature: The Imperial Legislative Council evolved into a bicameral body: the Legislative Assembly (144 members, 104 elected) and Council of State (60 members, 34 elected). Franchise expanded to about 5.5 million voters, though still limited.

- Provincial Legislatures: Enlarged with elected majorities (70-125 members), direct elections introduced, and communal electorates extended to Sikhs, Christians, and others.

- Executive Structure: The Viceroy’s Executive Council included three Indian members. Governors retained veto powers and could certify bills.

- Fiscal Autonomy and Review: Provinces gained some financial independence, and a provision for a review after ten years (leading to the Simon Commission in 1927).

The act aimed at progressive self-government but faced rejection by nationalists for insufficient powers and the continuation of dyarchy, which proved inefficient.

Government of India Act, 1935

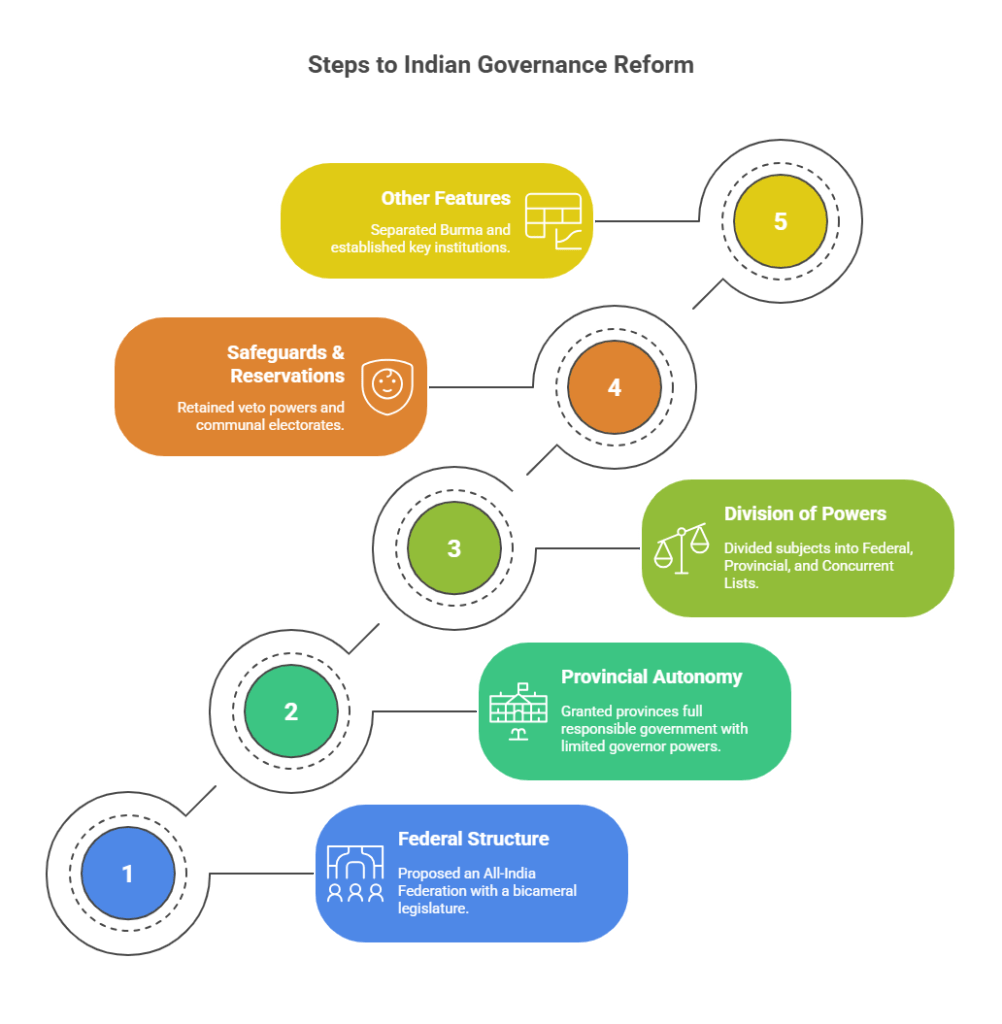

Enacted on August 2, 1935, this comprehensive legislation, based on the Simon Commission Report (1927), Round Table Conferences (1930-1932), and the White Paper (1933), represented the most extensive pre-independence reform. It sought to establish a federal structure while retaining British safeguards, responding to the Civil Disobedience Movement and demands for provincial autonomy.

Key provisions:

- Federal Structure: Proposed an All-India Federation including British provinces and princely states, with a bicameral federal legislature: Federal Assembly (375 members, partially elected) and Council of States (260 members, partially elected). The federation never materialized due to princely states’ reluctance.

- Provincial Autonomy: Dyarchy abolished; provinces gained full responsible government with governors’ discretionary powers limited to emergencies. Eleven provinces were established, with expanded franchises reaching 35 million voters.

- Division of Powers: Subjects divided into Federal, Provincial, and Concurrent Lists. The center controlled defense, foreign affairs, and currency, while provinces managed education, police, and agriculture.

- Safeguards and Reservations: Governors and the Viceroy retained veto powers, ordinance-making authority, and control over key services. Communal electorates persisted, with reserved seats for minorities, depressed classes, and women.

- Other Features: Burma separated from India; establishment of a Federal Court, Reserve Bank of India, and Public Service Commissions. Sindh and Orissa became separate provinces.

Implemented partially in 1937 (provincial sections), the act was condemned by the Congress for its federal scheme’s centralization and safeguards, yet it formed the basis for India’s 1950 Constitution.

Impacts of These Constitutional Developments

These acts had multifaceted impacts on India’s political, social, and administrative landscape, accelerating the independence movement while embedding certain legacies.

- Political Awakening and Nationalism: Expanded legislatures provided platforms for Indian leaders to voice grievances, fostering political education and unity. However, limitations fueled disillusionment, intensifying demands for full self-rule and contributing to movements like Non-Cooperation and Quit India.

- Communal Divisions: The introduction and extension of separate electorates (1909 onward) institutionalized religious divisions, strengthening the Muslim League’s case for partition and exacerbating Hindu-Muslim tensions, culminating in 1947’s division.

- Administrative Reforms: Provincial autonomy (1935) decentralized power, enabling Congress ministries in 1937 to implement reforms in education, agriculture, and labor, gaining governance experience. The acts modernized institutions, influencing post-independence federalism.

- Economic and Social Effects: Limited fiscal powers highlighted colonial exploitation, spurring economic nationalism. Reserved seats for minorities and women advanced representation, though unevenly.

- Criticisms and Shortcomings: Viewed as “divide and rule” tactics, the acts retained British vetoes, restricting true autonomy. The 1919 act’s dyarchy failed operationally, while the 1935 act’s federation collapsed, underscoring the need for complete independence.

Overall, these reforms transitioned India from direct colonial rule to semi-autonomous governance, but their inadequacies propelled the final push for sovereignty.

Key Features Comparison

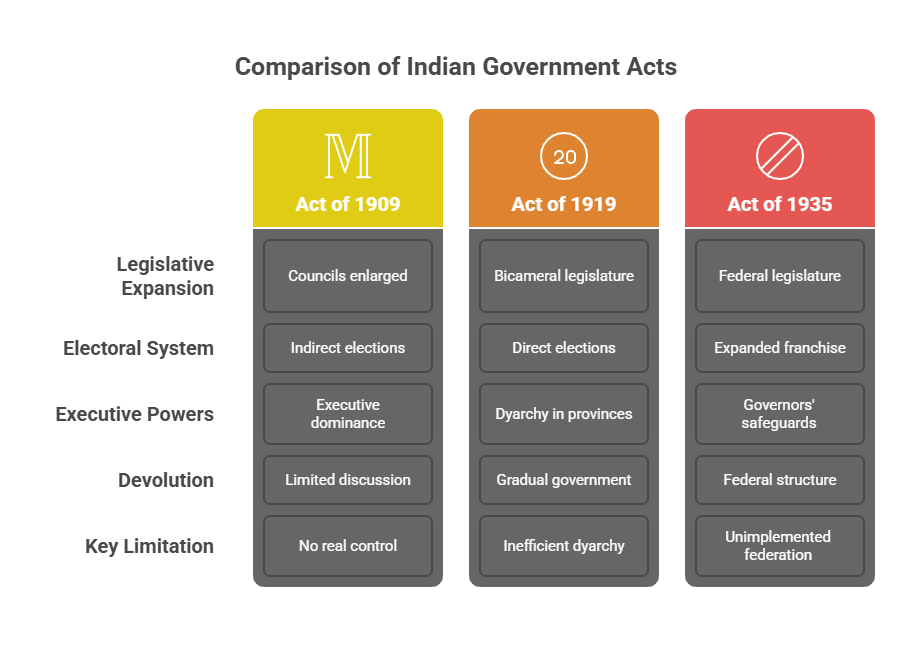

The following table compares the salient features of the three acts, highlighting their progressive yet limited nature.

| Aspect | Indian Councils Act, 1909 | Government of India Act, 1919 | Government of India Act, 1935 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legislative Expansion | Councils enlarged; non-official majorities in provinces | Bicameral central legislature; elected majorities | Federal bicameral legislature; provincial autonomy |

| Electoral System | Indirect elections; separate Muslim electorates | Direct elections; extended communal electorates | Expanded franchise; reserved seats for minorities |

| Executive Powers | Executive dominance; one Indian in Viceroy’s Council | Dyarchy in provinces; three Indians in Executive Council | Governors’ safeguards; full provincial responsibility |

| Devolution | Limited discussion powers | Gradual responsible government | Federal structure with lists of powers |

| Key Limitation | No real legislative control | Inefficient dyarchy | Unimplemented federation; central safeguards |

Legacy and Broader Impact

These constitutional developments laid the groundwork for India’s democratic framework, with the 1935 Act serving as a template for the 1950 Constitution (e.g., federalism, lists of powers, and emergency provisions). They heightened political consciousness, empowered regional leadership, and exposed colonial intransigence, ultimately contributing to the British exit in 1947. However, the entrenchment of communalism left enduring challenges, influencing post-partition relations and internal policies. This era exemplifies the interplay between reform and resistance in colonial transitions, underscoring the importance of inclusive governance in nation-building.

Leave a comment